You’ve done the math. Federal incorporation runs about $200, maybe $500 if you go provincial. A decent website costs $1,000 to $3,000. You can bootstrap the rest, right? Then reality shows up: professional liability insurance you didn’t know existed, accounting software subscriptions multiplying like rabbits, PST registration fees nobody mentioned, bookkeeping costs that seem absurdly high, and that’s all before your first customer pays you, which might take 60 to 90 days.

Here’s the uncomfortable truth most aspiring Canadian entrepreneurs face: they dramatically underestimate startup costs. Not because the information is hidden in some secret vault, but because they’re operating from a mindset that whispers “I’ll figure it out” or “that probably won’t apply to my situation.” This optimism bias sounds harmless until you’re three months in, personally funding everything, and wondering why you’re more stressed running your “freedom business” than you ever were in your corporate job.

This guide reveals the costs new founders consistently miss, why these blind spots exist, and how to budget realistically for a Canadian business launch without either overinvesting in nonsense or underinvesting in what actually matters. You’ll learn the difference between expenses that kill businesses and investments that build them. Whether you’re starting a coaching practice or launching any service-based venture, developing the right entrepreneurial mindset about money starts with seeing costs clearly, not optimistically.

Key Takeaways:

- The “hidden” costs aren’t actually hidden; they’re psychological blind spots where founders convince themselves “that won’t apply to me” until it does

- Cash flow gaps kill more Canadian startups than high expenses; three months of working capital isn’t enough when customers pay slow and expenses hit fast

- Insurance, professional fees, and compliance costs easily add $5,000-$15,000 annually, which most founders completely miss in initial budgets

- Your time has a cost if you spend 40 hours figuring out incorporation yourself to save $500, you’ve actually lost money at any reasonable hourly rate

- The founders who succeed don’t avoid costs; they face them honestly, budget realistically, and invest strategically in what actually moves their business forward

The Psychology Behind Missed Costs: Why Smart People Underestimate

Intelligence doesn’t protect you from bad financial estimates. I’ve watched brilliant professionals with MBAs and decades of corporate experience launch businesses on budgets that couldn’t sustain a lemonade stand. The problem isn’t stupidity. It’s psychology.

Optimism bias convinces you that you’re different, that you’ll somehow do it cheaper than everyone else managed. You read that the average coaching business needs $15,000 to $25,000 in startup capital, and you think, “Sure, but I already have a laptop and I’m great at networking, so I can do it for $5,000.” This isn’t strategic cost reduction. It’s wishful thinking dressed up as confidence.

Confirmation bias makes it worse. You research costs selectively, gravitating toward information that confirms your low estimates while dismissing higher numbers as “for people who don’t know what they’re doing.” You find one blog post from 2018 about starting a business for $500 and ignore ten recent articles saying $15,000 to $30,000. Your brain filters evidence to support the conclusion you want.

Present bias keeps you focused on immediate, visible costs while completely ignoring ongoing expenses that accumulate over time. You calculate the $300 incorporation fee but forget about the $150 monthly accounting software, the $2,000 annual insurance premium, the $100 monthly business banking fees, and the $500 quarterly bookkeeping costs. Those “small” recurring expenses compound into thousands annually, but they’re invisible in your launch budget because they don’t hit all at once.

Then there’s the DIY trap, the expensive belief that your time is free. You’ll spend 40 hours teaching yourself QuickBooks to avoid paying a bookkeeper $200 monthly. If your billable rate is $100 per hour, you’ve just traded $4,000 worth of time to save $200. The math is terrible, but it feels like winning because you didn’t write a check. This mindset keeps businesses small and founders exhausted.

The deepest issue isn’t math or information access. It’s limiting beliefs about money, creating cost blind spots. If you believe “spending money on my business is scary,” you’ll unconsciously avoid seeing expenses until they’re unavoidable emergencies. If you believe “successful people bootstrap everything,” you’ll sabotage yourself by refusing investments that would accelerate growth. Your money story determines what costs you see and which ones you’re psychologically blind to.

Understanding why businesses fail to scale often starts here: they launched underfunded, not because money wasn’t available, but because the founder’s mindset wouldn’t let them see or accept the real cost of building something sustainable.

Beyond Incorporation: The Legal and Compliance Costs Nobody Warns You About

Federal incorporation costs $200 if you file online through Corporations Canada, $250 if you mail it in. Add $13.80 for the NUANS name search report. Provincial incorporation varies: Ontario runs $300 to $360, BC costs $350 plus a $30 name approval fee, Quebec charges $326 plus $22 for name reservation, and Alberta hits $450 plus $30 for the name search. You see these numbers and think, “Okay, $500 to get incorporated, not too bad.”

That $500 represents maybe 20% of your actual first-year legal and compliance costs. Nobody tells you this part clearly enough.

Professional liability insurance, also called errors and omissions insurance, costs $500 to $5,000 annually, depending on your industry and coverage limits. Coaches, consultants, and anyone giving professional advice need this. You think, “I’m just starting, I’ll get it later.” Then you land your first real client, they ask if you’re insured, and you realize you can’t legally start work without it. Now you’re scrambling to buy insurance, which takes two weeks, and your client is wondering why you’re not ready to begin.

General liability insurance protects against property damage and bodily injury claims. If you meet clients in person or work from a commercial space, you need this too. Another $500 to $2,000 annually. “But I work from home!” Great, check your home insurance policy. Most specifically, exclude business activities, meaning your coverage might not apply if a client trips on your front steps coming to a business meeting.

Cyber liability insurance matters if you handle any client data electronically, which means virtually everyone. Data breaches, ransomware, privacy violations: these risks don’t care how small your business is. Add $1,000 to $3,000 for appropriate coverage, depending on how much client information you store.

Provincial licenses and permits vary wildly by industry and location. Some businesses operate with just incorporation. Others need multiple permits costing hundreds or thousands annually. Food service, healthcare, financial services, anything regulated, budget time researching what your specific business actually requires, not what you hope it requires.

HST/GST registration becomes mandatory once you hit $30,000 in revenue within any four consecutive quarters. You need to track this from day one because registration isn’t optional when you cross the threshold, and you’re liable for the tax whether you collected it or not. Most founders don’t set up proper systems until they’re already past the limit, creating instant tax debt.

Workers’ compensation coverage in some provinces applies even to sole proprietors in certain industries. Ontario, for example, requires coverage for independent operators in construction trades. BC has similar rules for specific sectors. Assuming “I don’t have employees, so I don’t need WCB” can be an expensive mistake.

The Insurance Nobody Budgets For

Insurance feels like throwing money away until the moment you need it, then it feels like the smartest purchase you ever made. The challenge is that “I’ll get it later” becomes “I need it yesterday” the moment a client asks about coverage, a contract requires proof of insurance, or something actually goes wrong.

Professional liability protects against claims of negligent work, errors in your advice, or omissions that cost clients money. If you’re a business coach and a client implements your strategy that fails, they could claim your advice was negligent. Without insurance, you’re defending yourself personally. With insurance, your policy handles the legal costs and potential settlement.

General liability covers physical accidents. Client trips and breaks an ankle at your office? General liability. You spill coffee on a client’s laptop during a meeting? General liability. You rent space for a workshop and accidentally damage the venue? General liability. These scenarios sound unlikely until they happen, and then they’re catastrophically expensive.

The real cost isn’t the annual premium; it’s the opportunity cost of not having coverage when you need it. That $2,000 insurance policy prevents the $50,000 lawsuit that closes your business before it really starts.

Getting your business banking setup properly is just one piece of the financial infrastructure puzzle. Insurance sits right beside it as non-negotiable infrastructure, not an optional luxury.

The Cash Flow Gap: Your Biggest Hidden Costs Aren’t an Expense

Most startup budget calculations look like this: “I need $10,000 for equipment, $5,000 for initial marketing, $2,000 for legal and incorporation. Total startup cost: $17,000.” This math is technically accurate and strategically worthless because it ignores time.

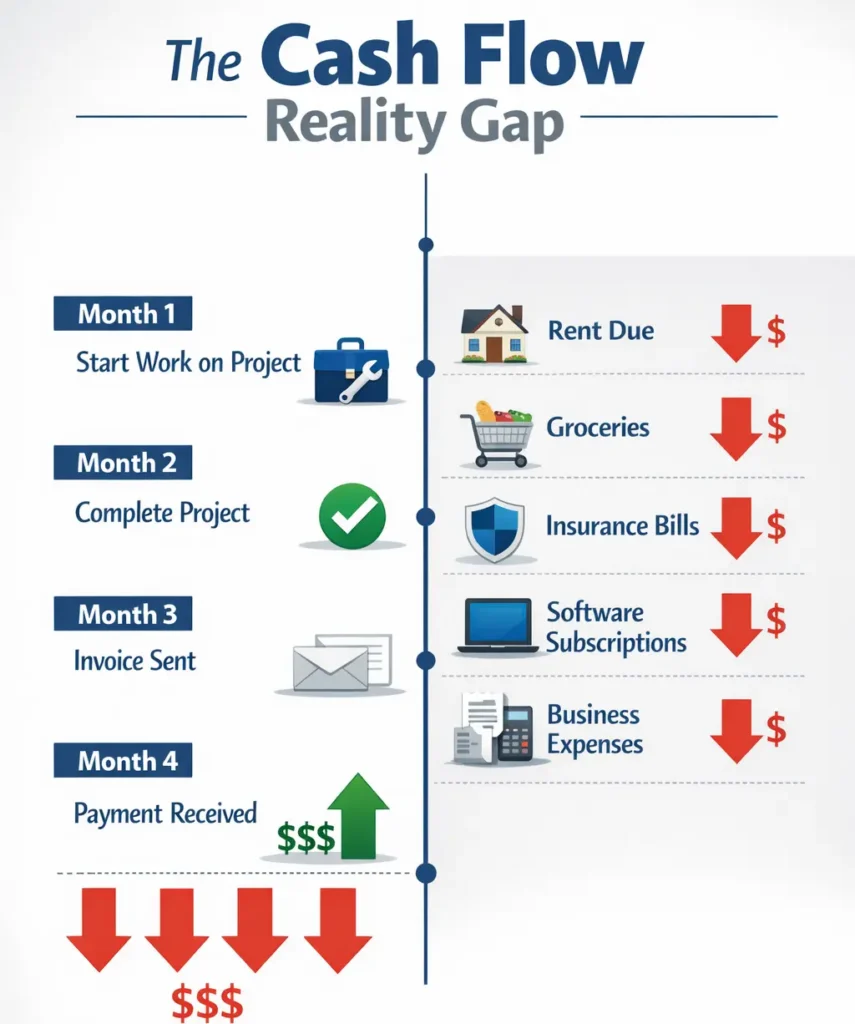

Here’s the question that actually matters: how long from when you start work until you receive payment? For many B2B service businesses, that timeline runs 60 to 90 days. You complete work in month one, invoice in month two, and if you’re lucky and the client pays on time with net-30 terms, you receive money in month three. More likely, they pay in 45 to 60 days, pushing your actual cash receipt into month four.

Meanwhile, your personal expenses don’t pause. You need $4,000 monthly for rent, groceries, insurance, car payments, and basic living. Your business has expenses too: that $150 monthly accounting software, the $100 business banking fee, website hosting, phone, internet, and marketing costs. Call it $1,000 monthly in basic business operating expenses before you even generate revenue.

Do the math: six months from business launch to consistent cash flow means you need $30,000 in personal runway ($4,000 x 6 months) plus $6,000 in business operating costs ($1,000 x 6 months). That’s $36,000 minimum before your first invoice gets paid, assuming everything goes perfectly and you land clients immediately.

Now add the psychological cost of financial stress. When you’re three months in, personal savings depleting, and your first big invoice is still 30 days from payment, you make desperate decisions. You discount heavily to close deals faster. You take on clients who aren’t quite right because you need the cash. You cut corners on marketing that would build long-term value. Financial pressure destroys strategic thinking.

One of my clients experienced exactly this pattern. Despite having consulting expertise and initial client interest, he felt completely blocked from leaving his corporate job to launch his practice. The block wasn’t a skill or market demand. It was unclear thinking about actual cash needs combined with limiting beliefs about financial risk.

Through our work together, he identified his “goal blocks,” the unconscious patterns keeping him stuck. We built a realistic six-month cash flow budget that included not just business costs but the full picture of personal and business needs. He saw clearly that he needed $40,000 in runway, not the $15,000 he’d vaguely estimated. That clarity shifted everything. Instead of launching scared and underfunded, he saved for another four months and launched from a position of confidence.

The insight that unlocked his progress: “Working with James really opened my eyes to the things that limit us in life…and keep us stuck. He talks a lot about goal blocks, and exposing these is half the battle.” Once he could see his money fears clearly instead of avoiding them, he built a plan that worked.

The biggest hidden cost isn’t an expense line item. It’s the gap between when you need cash and when cash arrives. Most founders calculate costs. Winners calculate cash flow timing.

What Are the Actual Incorporation Costs in Canada by Province?

Federal incorporation through Corporations Canada costs $200 if you file online, $250 if you mail paper forms. Add $13.80 for the mandatory NUANS name search report that confirms your chosen name is available and distinctive. Total federal cost: roughly $214 for DIY incorporation.

Provincial incorporation fees vary significantly. Ontario charges $300 for online filing through authorized service providers or $360 for in-person/mail filing. British Columbia costs $350 for the basic incorporation plus $30 for name approval, totaling $380. Quebec runs $326 for the declaration of registration plus $22 for name reservation, totaling $348. Alberta sits higher at $450 for incorporation plus $30 for the name search, totaling $480.

Manitoba costs $300 for incorporation plus $49 for the name search report if you want a named corporation. New Brunswick charges $290 total, including the incorporation fee and name search. Nova Scotia runs $336.40 for incorporation plus $118.35 for the registration fee, making it one of the pricier provinces at $454.75 total.

These are government filing fees, only the absolute minimum if you do everything yourself perfectly. Here’s what that DIY approach actually involves: understanding articles of incorporation requirements, drafting corporate bylaws, creating organizational resolutions, issuing share certificates, maintaining a corporate minute book, filing annual returns, understanding director and shareholder requirements, and ensuring ongoing compliance with corporate law.

Most founders spend 20 to 40 hours figuring this out, make mistakes that require amendments (another $100 to $250 each), and still end up hiring a lawyer later to fix things properly. Professional incorporation services range from $500 to $1,500, depending on complexity and what’s included. That sounds expensive compared to the $200 government fee until you calculate your time cost and error risk.

The real incorporation costs include ongoing requirements,s too. Annual returns, minute book maintenance, corporate record updates, registered office address maintenance, and director/officer reporting all carry costs and compliance obligations. In Nova Scotia, for example, incorporation certificates remain valid indefinitely, but registration certificates need annual renewal at $108.62.

Professional fees stack on top. Many founders hire lawyers for $1,200 to $1,500 to handle incorporation properly, including drafting shareholders’ agreements, employment agreements, and other foundational documents. Accountants charge $1,500 to $3,000 annually for corporate tax returns, significantly more complex than personal returns.

Then insurance: $500 to $5,000 annually, depending on coverage. Business banking with corporate accounts: $10 to $30 monthly in fees. Accounting software suitable for corporations: $30 to $70 monthly.

The $200 to $500 incorporation fee represents roughly 10% to 20% of your actual first-year costs related to operating as a corporation. The question isn’t whether you can afford the government filing fee. It’s whether you can afford the infrastructure, compliance, and professional support required to operate a corporation properly.

The Time-Cost Trap: When “Free” Actually Costs Thousands

Your time has economic value even when you’re not billing for it. This concept trips up smart people constantly because “doing it myself” feels free. You’ll spend 40 hours learning QuickBooks to avoid paying a bookkeeper $200 monthly. Seems frugal, right?

If your target billable rate is $100 per hour, common for coaches, consultants, and professional services, those 40 hours cost $4,000 in opportunity cost. You’ve traded $4,000 worth of potential revenue generation or skill-building time to save $200. The math is catastrophically bad, but it doesn’t feel wrong in the moment because you didn’t write a check.

This plays out everywhere. You spend 30 hours researching and attempting to design your own logo instead of hiring a designer for $500. At $100 per hour, you’ve just spent $3,000 of your time to save $500. Worse, the logo you create probably isn’t as good as what a professional would deliver, so you’ll likely redo it later anyway.

The DIY incorporation route is classic time-cost trap territory. Government filing fees run from $200 to $500. Professional incorporation services charge $500 to $1,500. Most founders choose DIY to save $1,000. Then they spend 25 hours navigating corporate law, make mistakes in their articles of incorporation, file incorrectly, need to file amendments, and still end up hiring a lawyer later to fix foundational documents. They’ve “saved” $1,000 while spending $2,500 worth of their time and creating legal risk.

Calculate Your Real Hourly Rate

If you plan to charge clients $100 per hour, your time costs $100 per hour right now, before you invoice anyone. Every hour you spend on tasks that could be delegated for less than $100 is expensive, even when you’re not paying cash.

The strategic question isn’t “Can I do this myself?” It’s “Should I do this myself, given what my time is worth?” Tasks that match or exceed your hourly rate: client work, business development, strategy, and building core intellectual property. Tasks that don’t: bookkeeping, basic graphic design, filing paperwork, scheduling social media posts.

This sounds obvious until you’re bootstrapping and cash feels scarce. Then you default to doing everything yourself because writing checks feels more painful than working 14-hour days. The psychology is backwards. Preserving your energy and focus for high-value work matters more than preserving cash through penny-pinching.

Decision fatigue compounds the problem. When you’re trying to be an expert in all areas of marketing, sales, operations, finance, legal compliance, technology, and customer service, you make worse decisions in all of them. You’re spreading mental bandwidth too thin to be effective anywhere.

The pattern that actually works: invest in professionals for areas outside your expertise, especially for high-risk domains like legal, financial, and tax matters. Bootstrap intelligently by doing what only you can do, and delegating or automating what someone else can do better or cheaper per hour.

Understanding how to measure business investments properly means calculating time costs, not just cash costs. The founders who scale successfully figured this out early. The ones who burn out trying to do everything themselves never did.

Strategic delegation isn’t an expense; it’s how you multiply your effective capacity beyond the 168 hours available per week. Business training programs teach these principles because they’re foundational to sustainable growth, not optional luxuries for when you “make it big.”

Subscriptions, Software, and Death by a Thousand SaaS Cuts

Accounting software runs $20 to $70 monthly, depending on features and business complexity. CRM systems cost $15 to $100 monthly per user. Email marketing platforms charge $15 to $300 monthly based on subscriber count. Website hosting and maintenance: $15 to $100 monthly. Productivity tools, project management platforms, file storage, password managers, social media scheduling, and video conferencing upgrades each seem reasonable individually.

Then you review your bank statement three months in and discover you’re spending $500 monthly on software subscriptions you don’t remember signing up for. That’s $6,000 annually disappearing into tools you use inconsistently or not at all.

The “I’ll just try it” trap works like this: you see a tool that solves a problem you have. Free trial for 14 days, then $29 monthly. You sign up, intending to evaluate it properly. The trial ends, automatic billing kicks in, you forget about it because it’s “only” $29, and six months later, you’re paying for software you opened twice.

Multiply this pattern across ten different tools. Accounting software you use monthly: legitimate expense. CRM system with features you haven’t configured: waste. Email marketing platform for a list of 47 people who haven’t opened an email in three months: waste. Productivity app that duplicates functionality you already have: waste. Social media scheduling tool you used once, then forgot: waste.

The real cost isn’t just the subscription fees. It’s the mental overhead of managing multiple platforms, the time spent learning tools you don’t fully adopt, and the opportunity cost of spreading your attention across too many systems instead of mastering a few.

Here’s what a realistic software stack looks like for a service-based business: accounting software ($40 monthly), CRM or simple contact management ($20 monthly), email marketing ($30 monthly), website hosting ($25 monthly), cloud storage ($15 monthly), and video conferencing ($15 monthly). Total: $145 monthly, or $1,740 annually.

That’s the baseline before industry-specific tools. Coaches might add scheduling software ($15 monthly). Consultants might need proposal software ($30 monthly). Content creators might add design tools ($20 monthly). Each addition should solve a clear problem and justify its cost through time savings or revenue generation.

The audit question to ask monthly: “If this software disappeared tomorrow, would I notice and care enough to replace it immediately?” If the answer is no or you hesitate, cancel it. The best way to manage subscription costs is ruthless pruning, not careful shopping upfront.

Tax deductibility helps, but doesn’t eliminate the cost. Software expenses are deductible business expenses according to CRA, reducing your taxable income. But that means you save your marginal tax rate on the expense, maybe 25% to 35%. You’re still spending 65% to 75% of the subscription cost even after the tax benefit.

Treat software budgets like hiring decisions: every subscription represents a recurring commitment. Before you add one, ask whether it solves a real problem better than alternatives, whether you’ll actually use it consistently, and whether the time savings or capability gain justifies the ongoing cost.

How Much Working Capital Do I Actually Need?

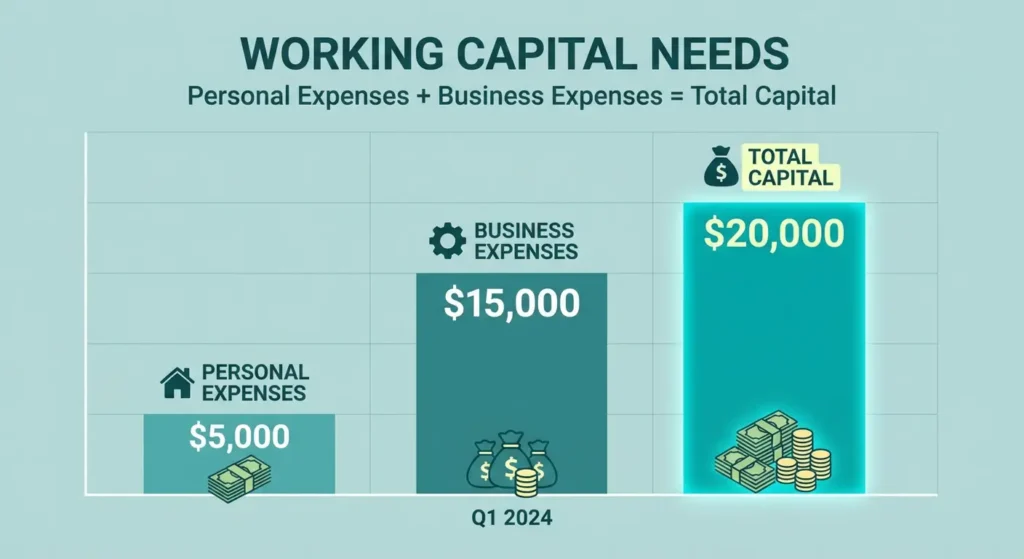

Calculate your monthly personal expenses: rent or mortgage, groceries, utilities, insurance, car payment, minimum debt payments, and basic living. Be honest, actual spending, not aspirational minimalism. Let’s say that’s $4,000 monthly.

Multiply by 6 to 12 months. That’s your personal runway: $24,000 to $48,000. This is how long you can sustain yourself with zero business income.

Now calculate monthly business operating costs: accounting software, website hosting, insurance (divide annual premium by 12), business banking fees, marketing budget, professional association dues, continued education, subscriptions, and any equipment leases. Even a lean service business runs $500 to $1,500 monthly in baseline operating expenses before you generate revenue. Use $1,000 monthly as a reasonable estimate.

Multiply business expenses by 3 to 6 months: $3,000 to $6,000 minimum.

Add personal and business numbers together: $27,000 to $54,000 in required working capital before launch if you start with zero clients and zero revenue.

“But I’ll have clients before I launch!” Great adjustment for confirmed revenue with realistic payment timelines factored in. If you have a client committing to $5,000 in work starting in month one, don’t count that as available cash in month one. With typical B2B payment terms, that money arrives in month three or four. Reduce your working capital needs by that amount, but time it correctly.

The three-month runway myth kills businesses. “I’ll give myself three months to make this work” sounds bold and action-oriented. It’s actually desperate and underfunded. Most service businesses take three to six months just to establish consistent client flow, and another three to six months before payment cycles create reliable cash flow. Launching with three months of runway means you’re financially stressed from day one, making decisions from fear rather than strategy.

Provincial differences matter for payment timelines. Quebec’s construction industry has legislated prompt payment requirements. Federal government contracts often take 60 to 90 days to process payment even after invoice approval. Large corporations routinely pay net-60 or net-90 terms. Small businesses might pay faster but also might struggle with cash flow themselves, delaying your payments.

Why the “start with what you have” advice can be dangerous: it assumes you can generate revenue fast enough to cover expenses before your savings run out. For some businesses, freelancing with existing clients, consulting with confirmed contracts, this works. For most new ventures building from scratch, it creates a ticking financial time bomb that explodes in month four when savings deplete, and revenue hasn’t materialized yet.

The psychological impact of launching an underfunded program is massive. Financial stress destroys decision quality. When you’re worried about making rent, you can’t think strategically about building a sustainable business. You chase any paying work instead of ideal clients. You discount pricing to close deals faster. You skip investments in marketing and infrastructure that would build long-term value. Desperation becomes your operating mode, and clients can smell it.

Here’s the honest assessment: if you need $4,000 monthly personally and $1,000 monthly for business operations, and you’re starting from zero clients, you need a minimum of $30,000 to $50,000 in accessible working capital before you launch. If you have confirmed clients and contracts that will generate $3,000 monthly starting in month one (with month three payment expectations), you need $20,000 to $30,000 in working capital.

Less than that, and you’re hoping, not planning. Hope is an expensive business strategy.

The Professional Fees Everyone Forgets Until They Need Them

Accountants and bookkeepers cost $1,500 to $5,000 annually for basic small business services: monthly bookkeeping, quarterly financial statements, annual tax return preparation, and basic tax planning advice. “I’ll use accounting software and do it myself!” works until tax time arrives and you realize you don’t understand capital cost allowance, when to recognize revenue, how to handle PST/GST remittances, or what business expenses are actually deductible.

The DIY approach costs you in three ways. First, time probably 10 to 20 hours monthly tracking transactions, categorizing expenses, reconciling accounts, and generating reports. That’s 120 to 240 hours annually, worth $12,000 to $24,000 at a $100 hourly rate. Second, accuracy mistakes cost money through missed deductions, incorrect tax calculations, or failed CRA audits. Third, an opportunity a good accountant provides tax planning that saves multiples of their fee through strategic expense timing, income splitting, and credit utilization.

Lawyers for contracts, terms of service, privacy policies, and foundational documents: $500 to $3,000 for initial setup, more if you need ongoing contract review. “I’ll use a template I found online!” works until a client dispute arises and you discover your terms of service aren’t enforceable, or your contractor agreement doesn’t actually protect your intellectual property, or your liability waiver doesn’t comply with provincial requirements.

Business coaches or consultants range from $5,000 to $20,000 annually, depending on engagement depth. This feels like an enormous expense until you calculate what bad decisions cost. A coach who helps you clarify positioning, avoid common scaling mistakes, and build sustainable systems can save years of trial-and-error learning and tens of thousands in revenue lost to poor strategy.

Industry certifications and ongoing education vary by field. Coaches might spend $5,000 to $15,000 on ICF accreditation or specialized training. Consultants invest in industry-specific certifications. Even general business owners benefit from courses on financial management, marketing, operations, and leadership. Budget $2,000 to $10,000 annually for staying current and building capabilities.

Professional association memberships, networking groups, and business organizations: $500 to $2,000 annually. These feel optional until you realize how much business development happens through relationships and referrals. The right associations provide education, connections, and credibility worth multiples of membership fees.

Why cutting these costs usually costs more later: professional fees prevent expensive mistakes. A lawyer reviewing your first major client contract for $500 might spot a liability clause that would have cost you $50,000 in a dispute. An accountant setting up proper bookkeeping from day one prevents the nightmare of reconstructing a year of transactions from bank statements when CRA audits you. A business coach helping you avoid one bad hire saves months of stress and thousands in recruiting costs.

These aren’t expenses you’re forced to bear; they’re investments in not making catastrophically expensive mistakes. The founders who resist professional help often do so from limiting beliefs: “I can’t afford it yet” (you can’t afford not to), “I’ll get help when I’m bigger” (by then, you’ve baked in costly problems), or “I should be able to figure this out myself” (sure, if you want to pay tuition to the school of expensive experience).

Smart entrepreneurs invest in professional guidance strategically. They don’t hire everyone for everything; they identify high-risk, high-complexity areas where expertise matters most. Legal? Hire a lawyer. Financial? Hire an accountant. Strategy and scaling? Work with a business coaching support professional who’s built what you’re trying to build.

Calculate the real cost formula: professional fee minus mistakes prevented, minus time saved, minus decisions improved. The math usually shows professional fees as some of your highest-ROI business investments.

Should I Incorporate Right Away or Start as a Sole Proprietor?

Start as a sole proprietor if your expected annual revenue will be under $50,000, you have minimal liability risk in your industry, and you want to test your business model without additional complexity. Registration costs $30 to $150, depending on province, versus $200 to $500+ for incorporation. You file one tax return instead of two. Accounting is simpler. Administrative overhead is minimal.

Incorporate when liability protection matters, you’re hiring employees, annual profit will exceed $50,000, where corporate tax advantages kick in, or you need credibility with larger clients who prefer working with incorporated businesses. The $300 to $500 incorporation cost itself isn’t the decision point; it’s the ongoing complexity, compliance requirements, and professional fees that come with operating a corporation.

Tax implications shift significantly once profit exceeds $50,000 annually. The small business corporate tax rate in most provinces ranges from 11% to 15% on the first $500,000 of active business income, compared to personal income tax rates that climb above 30% once you include provincial tax. That 15 to 20 percentage point difference means significant tax savings on retained earnings.

But those savings only materialize if you leave money in the corporation for business reinvestment or retirement savings. If you pay everything out to yourself as salary or dividends immediately, much of the tax advantage disappears. Incorporation makes sense when you’re earning more than you need to live on and can benefit from income splitting, lower corporate tax rates, and tax deferral strategies.

Liability protection differences matter most in professional services, consulting, coaching, and any industry where your advice or work product creates risk of client claims. As a sole proprietor, you and your business are legally the same entity. Business debts are your personal debts. Someone sues the business; they’re suing you personally, and your home, car, and savings are vulnerable.

Incorporating creates legal separation. The corporation owes the debts and faces the lawsuits. Your personal assets generally remain protected unless you’ve personally guaranteed business obligations or acted negligently or fraudulently. That liability shield has real value if you’re in a sector where professional claims are common.

Credibility and perception play roles in B2B services. Some larger corporate clients have policies requiring vendors to be incorporated. Government contracts often prefer or require incorporation. Professional service firms sometimes view sole proprietors as less established or serious. This isn’t fair or necessarily logical, but it affects your ability to win certain work.

When the complexity of incorporation isn’t worth it yet: if you’re testing a side business while employed full-time, if annual revenue will be under $30,000, if you’re providing very low-risk services, or if you’re genuinely unsure whether the business model works. Start simple, validate the model, then incorporate when growth and risk profiles justify the added structure.

The transition from sole proprietor to corporation is straightforward. You can operate for one or two years as a sole proprietor, then incorporate when it makes sense. You don’t need to incorporate on day one unless liability risk or credibility requirements demand it immediately.

Practical advice: most service-based businesses should incorporate once they’re confident the business will continue, once annual profit approaches $50,000, or once they need the credibility and liability protection. Before that threshold, a sole proprietorship keeps things simple while you validate and build.

Hidden Psychological Costs: The Expenses That Don’t Show on Balance Sheets

Decision fatigue from constant cost-cutting destroys your cognitive capacity. When you’re perpetually asking “Can I afford this?” about every $30 expense, you burn mental energy on questions that don’t matter. You’ll spend an hour researching whether to buy a $50 software subscription instead of spending that hour talking to potential clients or refining your service offering.

This shows up everywhere: agonizing over whether to spend $200 on business cards, debating a $15 monthly scheduling tool for weeks, choosing the cheapest accounting software even though it lacks features you need, refusing a $30 monthly CRM because you convince yourself a spreadsheet is fine. Each individual decision seems financially prudent. Collectively, they create a mindset of scarcity that prevents you from thinking and acting strategically.

Relationship strain from financial stress compounds fast. Partners, families, friends, everyone feels the weight of your launch anxiety. You’re irritable because you’re worried about money. You’re unavailable because you’re working constantly trying to bootstrap everything. You decline social invitations to save money. The relationships that should support you through the challenging early phase start cracking under stress instead.

Health impacts of chronic money worry are measurable and expensive. Sleep degrades. Stress hormones stay elevated. You make worse decisions because you’re operating from fight-or-flight physiology instead of strategic thinking mode. You eat poorly because healthy food feels expensive. You skip the gym to save the membership fee, sacrificing the stress relief and physical health that would help you perform better.

Opportunity costs of playing it “too safe” might be the highest invisible expense. The founder who won’t spend $5,000 on proper branding and website development because “I need to conserve cash” often spends two years struggling to attract premium clients because they look amateurish. They’ve “saved” $5,000 while losing $50,000 in revenue they could have earned with proper positioning.

The cost of staying small to avoid expenses is exponential. You don’t hire the assistant who could free up 10 hours weekly for business development. You don’t invest in marketing that would generate consistent leads. You don’t join the mastermind group where you’d learn from others five years ahead. Each avoided expense feels like winning, but collectively, they guarantee you stay stuck at your current revenue level.

The NLP Perspective on Money Blocks

The founder who won’t invest $1,000 in professional branding but spends 100 hours on DIY design has a money story problem, not a cash problem. Somewhere in their belief system sits a narrative: “Spending money on my business is dangerous,” or “Real entrepreneurs bootstrap everything,” or “I’m not worthy of investing in myself yet.”

These beliefs create behavioral patterns that look like frugality but function as self-sabotage. You’ll avoid the $2,000 business coach consultation that would save you $20,000 in mistakes. You’ll refuse the $500 professional headshots that would dramatically improve your credibility and conversion rates. You’ll skip the $3,000 mastermind that would surround you with peers solving the same challenges you face.

The cost isn’t the money you don’t spend. It’s the growth you don’t achieve because your money story keeps you playing small.

Breaking through limiting beliefs about money and investment is often the real work of early-stage entrepreneurship. The technical and tactical pieces, incorporation, software selection, and pricing models are straightforward. The psychological piece facing your relationship with money, risk, and worthiness determines whether you build something sustainable or stay stuck in perpetual struggle mode.

Breakthrough limiting beliefs isn’t optional personal development work for when you “have time.” It’s a foundational business strategy because your mindset determines which costs you see as investments versus which ones trigger fear and avoidance.

Conclusion

Hidden costs aren’t hidden. They’re just uncomfortable to acknowledge because doing so means facing how much building a real business actually requires. Most failed businesses didn’t fail from spending too much; they failed from underinvesting in the infrastructure, support, and working capital required for sustainable growth.

The founders who succeed share a pattern: they budget honestly, they invest strategically, and they build from actual financial truth rather than wishful thinking. They don’t avoid expenses; they differentiate between costs that drain resources and investments that build capacity.

You now know what new founders consistently miss: insurance adding $2,000 to $10,000 annually, professional fees running $3,000 to $10,000, software subscriptions accumulating to $2,000 to $6,000, and cash flow gaps requiring $30,000 to $50,000 in working capital. These numbers might feel overwhelming. They’re actually empowering because now you can plan realistically instead of launching hopefully.

Calculate your real startup cost,s including working capital, insurance, professional fees, and your time valued properly. Add 20% for things you’re still not seeing. That’s your honest number. If you don’t have it yet, you know what to save toward. If you do have it, you can launch from confidence instead of desperation.

The businesses that win don’t avoid costs; they face them clearly, invest strategically, and build from financial reality rather than financial fantasy. That mindset shift, more than any tactical cost-saving strategy, determines who builds something sustainable versus who burns out trying to do everything on a shoestring.

Ready to launch your business with financial clarity instead of anxiety? Discover how business coaching and NLP training can help you break through money mindset blocks and build a profitable venture from day one, not year three.

FAQs

What are the hidden costs of starting a business in Canada?

Beyond incorporation fees, new founders often miss recurring costs like insurance, professional fees, compliance filings, accounting software, and business banking. Cash flow gaps and delayed payments also create financial pressure that many don’t plan for. These “invisible” expenses often exceed the initial launch budget.

How much does it really cost to start a small business in Canada?

A lean service-based business may require $30,000–$50,000 in working capital when factoring in personal runway, operating expenses, professional fees, and cash flow lag. Many founders underestimate startup needs by only budgeting for equipment and incorporation instead of ongoing financial infrastructure.

Is incorporation in Canada worth it for new entrepreneurs?

Incorporation offers tax advantages, liability protection, and credibility, but the government filing fee is only part of the cost. Corporations must maintain minute books, file annual returns, manage professional accounting, and secure insurance, together forming 80–90% of true year-one costs.

What business expenses do new Canadian founders overlook most?

Commonly overlooked expenses include liability insurance, bookkeeping, tax filings, corporate renewals, software subscriptions, business banking fees, and marketing tools. The highest hidden cost isn’t an expense at all; it’s the cash flow gap between when work starts and when payment arrives.

How much working capital do I need before launching a business in Canada?

Most founders need 6–12 months of personal runway plus 3–6 months of operational costs. For many service businesses, that means $30,000–$50,000 in accessible capital to avoid making desperate decisions, discounting, or taking misaligned clients under financial pressure.